Zoë Pollak Humanities

The World in the Globe of the Eye: Reading Housekeeping Through a Thoreauvian Lens

Current Bio: Zoë is a PhD candidate in English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University (MSt in English from Oxford [2016]) writing a dissertation on small forms in 19th century poetry.

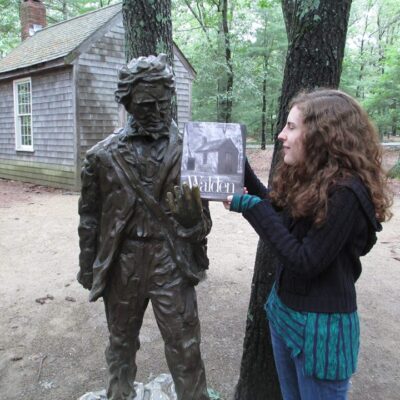

Haas Scholars Project: More than once, Marilynne Robinson has invoked Henry Thoreau’s Walden (1854) as an influence on her novel Housekeeping (1980). Zoë’s project investigates the philosophical resonances between these two texts written in the tradition of American Romanticism. Rather than wed Walden to history and read Housekeeping as a modern-day (and specifically feminist) response, Zoë develops a more fluid relation between the two testaments to spiritual solitude. By placing the books in conversation, Zoë explores the relationship between the invention of audience and inwardness. She also asks how the depiction of place can inform a writers persona on the page and vice versa. Zoë’s thesis derives its larger metaphysical context from 19th-century articulations of nature and the sublime, and considers the influence of English Romantics like Wordsworth and Keats on Walden and Housekeeping.

Scholars Journal

Instead of trying to capture everything about my trip to Concord, I'll reference the highlights. Without question, my favorite part was the walk around Walden itself. I heard that the pond would be swamped with tourists and swimmers and that its size is much smaller than a

Walden reader might be led to believe based solely on the time Thoreau spent crafting the water in elaborate conceits and analogies. As it turned out, Walden was almost bare the day I visited, as it was overcast and drizzling -- the best atmosphere in my opinion, as gray skies bring out the green in the leaves. Some images I plan on taking with me: the rain dimpling the surface of the water, the difference in color between the darker water in the middle of the pond and the reflections of the trees on Walden's edge (the lashes bordering the eye of the pond, Thoreau wrote), and the way the trees on the trail filtered the sun like stained glass.

.

At the end of the trip I had a brief chance to visit Salem. I took a tour of Nathaniel Hawthorne's birth house and the House of the Seven Gables (the latter inspired his eponymous novel). Surprisingly, I think seeing the House of the Seven Gables was the most intellectually fulfilling part of my time in Massachusetts because it allowed me to begin synthesizing the ideas I'd been developing over the course of my time in Concord.

The House of the Seven Gables has a different history than the Concord homes I visited, a much more self-consciously literary one. Unlike the Alcotts' Orchard House and the Emerson family home, both of which, from the furniture to the portraits on the walls, are presented as relatively preserved, the House of the Seven Gables' history of renovations is an important part of the tour. Our guide explained that while the time Hawthorne spent visiting his cousin in the house clearly informed the way he portrayed it in his novel, the literary version of the structure's architecture is embellished. After Hawthorne died, a wealthy woman purchased the property and added a wing in the kitchen for one of the characters and a secret staircase for another to conform to the house Hawthorne presents in the novel.

.

Given its multiple renovations, most of the House of the Seven Gables' interior is from more recent centuries. There are a few areas, however, where you can see its 1668 foundation. In one room, the rafters that jut toward the ceiling have supported the roof for over three hundred years. And upstairs, a large part of the wall has eroded to reveal its core: weathered bricks sustained by a series of planks: the house's ribs. The walls' bareness made me think of a diagram in an anatomy textbook in which the body is peeled into layers of skin and tendon and bone. It seemed vulnerable and intimate. Yet the interior, however worn, is the house's most enduring structure.

I have been thinking about layers ever since I walked Walden. Since Thoreau's day the woodland has been leveled, probably more than once. Crops of trees have been cut and burned down and new ones have sprung up in their place. I couldn't find one trunk with the thickness of a century. And then there are the smaller, inevitable cycles: the rains and evaporations; the scattering of leaves as the seasons revolve.

.

I may have walked Walden, but it wasn't the one in Thoreau's book. The skins of Concord's houses have been stripped and re-layered; the pond and its woods have shed and grown. The nearer I feel to the past the more boundaries I find. In

Walden, Thoreau writes that the farther conversants sit from one another, the deeper their communication. Reading him has made me realize that I, too, have to get farther from something to feel closer to it. Writing affords that intimate expanse. To determine the life of a tree, you'd have to cut through the center and count the rings. Better to let it live in books, and not measure the distance.